Who is in charge of the castle, should be in charge of the heritage, and should take care of it even if he had to fight for it (Kamal Jomblat). [1]

Leadership is a controversial issue in the Arab world and especially in Lebanon, considering the sectarian nature and diversity that have always been characteristics of the country. Leaders in our country enjoy great popularity within their own territory; whether this territory is an area of origin that goes back hundreds of years, or a more limited geographical area such as individual districts, cities or even the "hayy" or neighborhood. The inheritance of power from one family member to the next is something that has become normalized in Lebanon. A specific leader/family represents each sect, and the same familiar families have held this leadership for decades. The Gemayels, Jomblats, Geageas, Aouns, Mouawads and others have monopolized politics in Lebanon since the pre-civil war years. These families staunchly guard their right to leadership. Is it because these families have enough qualifications that enable them to take such important positions? Is it the people's choice? Is it parties' choice? Do their followers believe in their leader's ideologies, or is it something so naturalized that we do not even bother to question?

An interesting issue that arises from this is that of the inheritance of leadership. The son assumes leadership, or "za'ameh", after his father, even if the son has nothing to do with politics and never wished to go into such a career. Here I would like to start with the specific historical example of the Jomblat family, and compare it to a more contemporary example: that of the Hariri family.

From the day he was born, on December 6, 1917, it was decided that Kamal Jomblat was going to inherit the position of leadership from his father. When his father was assassinated on August 6, 1921, Kamal Jomblat was still a child. For the first time in Druze history a woman was in charge of the community. Lady Nazira, Kamal's mother, insisted on assuming this role for one reason, to save the leadership for her son until he became old enough to do so himself. Kamil Abu Suwwan, one of his old school friends, remembers how teachers used to talk about the special instructions that were given concerning Kamal's situation. He remembers how a special servant, who was 35 years old at that time, always accompanied him. Even at night, his servant used to sleep on the bed next to the future leader.[2] Even at 4 years old, the religious Druze figures, al-masheyekh, used to call him 'ya sidi', or 'my master'. At big lunches that used to be held in the Mokhtara castle, each time his mother talked about a political subject, she used to turn to him and ask him about his opinion, even when she knew that he was still too young to understand such issues. He did not like politics and was hesitant to get into it. But when he realized that he could do so much for the Druze community in general, and for the Jomblat family in particular, and after the insistence of his mother and her various trials to convince him through family friends that she trusted, he accepted. Directly after this, people from the mountain came in large numbers to announce their allegiance to the new leader, a leader who was not even part of the government yet.[3] This tradition goes back 300 years, when the Jomblat family began their involvement in Lebanese political life, creating political parties that involved figures from all around Lebanon, with a basic aim of achieving a secular Lebanon.[4]

In contrast, the Hariri family falls into a totally different category of leadership. Rafik al Hariri is a leader that represented the decade of post-civil-war reconstruction of Lebanon, Beirut in particular.[5] Unlike Kamal Jomblat, who came from a family of leaders, Rafik al Hariri didn't come from a historically popular family. His father was a normal merchant who lived in Saida, which was far removed from the forefront of development of any sort. Rafik al Hariri grew up in the epoch of an emerging Arab nationalist identity, where young people were drawn to the vision of Egypt's Jamal Abdul Nasser, and where discussions of anti-Western political theories and debates over the rights of people filled the cafes and universities. Some say that he used to participate in political activities, but his main focus was on acquiring a business education so he could earn a living."[6] After he earned his certificate, he had to abandon higher education for lack of funds. Having acquired his wealth abroad, in Saudi Arabia, he came back to Lebanon and started donating money to boost infrastructure in his hometown. Although small in comparison to the educational investments of a few years later, "the donation to the school in Saida was the key experience in the formation of his awareness of social needs and public service", he said.[7] The next moves in his charitable contributions carried on and his philanthropic endeavors became his defining characteristic.

In 1978, he built a new center of education, healthcare, and cultural development in his home area. In parallel, he established a foundation for funding school and university education for deserving students. His mission extended to preserving Lebanon's cultural and architectural heritage, besides providing educational grants and other assistance to applicants from all religions[8]. After he played a major role in the Taif agreement, and in the face of waning confidence in the economy of post-war Lebanon, "the Lebanese responded enthusiastically to the prospect of the outsider and symbol of the economic success stepping up to the nation's helm. It was a sign of the times that the man who stood behind the signing of the Taif agreement that halted the 17 years of war was now adorned with every title of hope that a person can think of". The people who had experienced 17 years of war, whom were then told that one man had stopped the war and silenced the guns, perceived him as a savior and light of hope.

Unlike Kamal Jomblat, whose leadership was directly attached to his area of origin, Rafik Al Hariri moved his seat of residence from Saida to Beirut. This surprised many of his supporters because it represented a break in Lebanon's political tradition, under which elected leaders were careful to maintain and nourish the roots in their hometown or native district[9]. Hariri's decision to leave his area of origin denaturalized the inheritance of leadership when compared to the inheritance of Jomblat. Conversely, Kamal Jomblat's decision to remain in his area of origin facilitated the future passing of leadership on to his son.

After the assassinations of the father-leaders, attention was directly turned towards the leaders' sons. All this was obvious in media coverage: the son meeting all the important political figures, sitting side by side next to his father's allies, representing his father's party or organization when being interviewed, and finally being introduced into the commemorative posters that were produced after the leaders' assassinations. The posters, although so different in the constituent elements, all had the same main message or aim, which was to legitimize the son's inheritance of leadership from his father. For the Jomblat family, this was not the first time someone inherited leadership, and it had become a kind of tradition. For the Hariri family, the son was the only person who could continue in the father's footsteps of wealth, charity, and reconstruction of Lebanon. This obviously shows how Hariri's role was conceived as that of a statesman with wealth, rather than that of a traditional "za'im" like in the case of Jomblat.

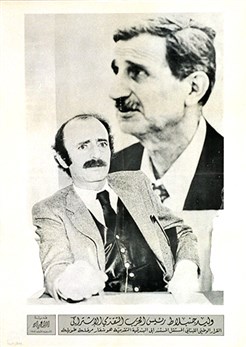

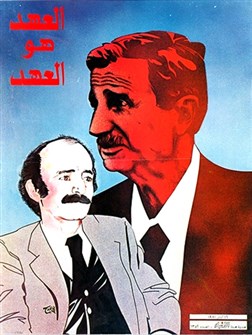

Concerning the posters that were produced after the assassination of Kamal Jomblat, I would like to emphasize a couple of posters that are simultaneously similar and different when compared to the posters of Hariri. The first is a photograph (fig. 1) that was put in the parties' newspaper, al Anbaa, in 1981, and was then transformed into an illustrated commemorative poster (fig. 2) later that year on the same day of the leader's assassination. Slight manipulations were made in its transformation into a commemorative poster. The first and most obvious aspect is the presence of both the father and son, with the father placed in the background and the son in the foreground. At the time of the assassination of the father-leader, Walid Jomblat only represented the leader's son; he was not yet known as a political figure. The Lebanese population was not even familiar with his image. This is one of the reasons why he could not be represented alone. Furthermore, his representation with his father in the background legitimizes him as the next leader.

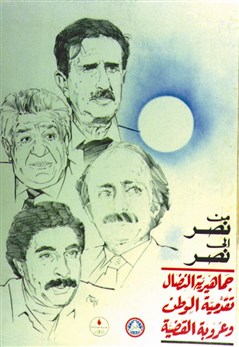

I would like to highlight some interesting points in these posters that will help compare and constrast them with the analysis of the Hariri posters. Jomblat leaders are never depicted perfectly posing in photographs; it is always a photograph that was taken spontaneously while they were working, thinking, or worrying, even if they wore suits and neckties (fig. 3). Even in illustrated posters, they are represented as leaders with wrinkles on their foreheads and with undone hair (figs. 4 and 5). One could relate this undone look to the leftist political inclination of Jomblat the father, founder of the Progressive Socialist Party. Kamal Jomblat was seen as a humble leader who used to sit on the floor and eat with his visitors. He changed all the 'prestigious' acts that were present in his family before he became leader.

The images for Hariri leadership, although similar in context, can be divided into three major groups based on the date of their production. Starting with the day of assassination of the father leader and the few days that followed including the leader's funeral, moving to the elections period that followed this assassination, and finally the commemorative posters of the father-leader. One clear message that can be seen, just like the Jomblat posters, is the legitimization of Saad al Hariri assuming leadership after his father's death. But this is not the ultimate and only message behind these images. I am going to look at the first level, denoted messages, and then move to uncover the connoted meanings, analyzing each intended message separately. Finally, I will examine the broader discourse when all the messages combine to form one unified message.

For the Hariri posters, the categorization of the production dates that I mentioned is interrelated, with a few exceptions. The posters that came out directly after Rafik Hariri's death were also used in the election campaign of his son Saad, as well as on the one-year anniversary of his death in 2006. First, I will deconstruct the images and highlight the common elements in all of the Hariri posters, and simultaneosly point out specific points in each poster that distinguished it from the others.

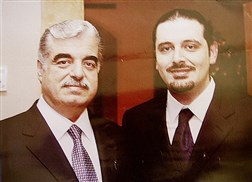

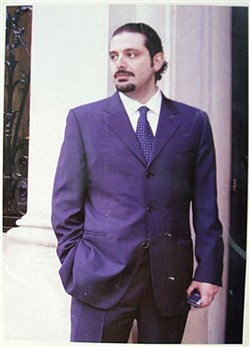

One common aspect is the business suits the Hariri leaders, both father and son, wear in their portraits (figs. 6 and 7). Rarely are either of them depicted in everyday clothes. This formal dress code associated with their wealth is emphasized over and over again. This image is reinforced by the posture they assume while photographed. It is always a picture-perfect image: hair perfectly done, clean and freshly-shaven faces, and perfectly tied necktie.

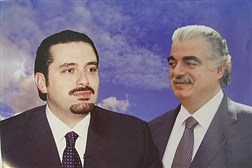

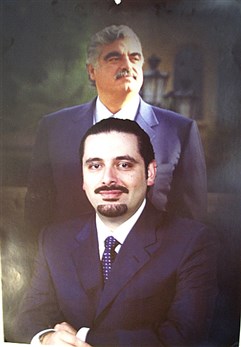

Another common aspect is the look on the father's face. He is always depicted either looking ahead with a very confident, assertive, and proud look, or towards his son who is preparing to take his role (figs. 6 and 8). This distant gaze is one towards the future (fig. 9), in particular the future of Lebanon, as he was always concerned with building a new Lebanon out of the ruins of the war. It is also an assertive gaze of power. The second look that is towards his son is one full of pride, pride of what he has left behind him, his son. I would like to pinpoint this one in particular, which unlike all the others in which Rafik Al-Hariri's photo is used, was taken directly before his death (fig. 6). The last photographs of him at the parliament were exactly the same. He is placed against a sky background with his son, with sunlight lighting his head and shoulders (fig. 8).

This gets us to a third common element that is noticed throughout most of Hariri posters, which is the light hitting the father, where it could be interpreted in two ways according to the different posters. For example in the poster with the sky background (fig. 8), the light is coming from above, illuminating his white hair, making it almost glow with his shoulders. On the other hand, his son has no light on any part of him. On the connoted level, the context that the father is put in may be a reference to the afterlife; glad with what he did and whom he left behind to continue the journey. The use of light in the other posters has a different meaning. The father is used in this case as a source of light, lighting the way for the new leader. The poster where the father is standing behind his son (fig. 9) is almost dark without the light coming from behind. It is a source that is lighting the father's face and the darkness in the foreground, the son's world, as if the father is paving the way for his son's journey. What is interesting in this is the way Saaddine al Hariri is posing for the photograph. He is posing for his political campaign, but another layer is added, one that is not usually present in common political campaigns. Another common look that Saaddine has is that of the sad dreamer, particularly in the blue-sky poster (fig. 8). He is depicted as still in the mourning stage, but at the same time entering the political field, doing an interview (microphone on his jacket). He has taken his father's place and is staring hopefully towards the future. The background of this poster also deserves analysis. The blue sky is divided into two parts: the clear sky is placed behind the father, whereas the partly cloudy sky is placed behind the son. This may be implying that while the father is at peace, the son will face troubles and obstacles that will appear along his journey to leadership.

Composition wise, the posters containing both father and son could be divided into two categories; one where the two figures are at the same level and given the same amount of importance (figs. 6 and 8), and another where the father is given more importance and is placed in a second background layer, supporting that of the son (figures 9 and 10). In the posters where the father is placed in the background, a montaged perspective could be noticed. It is true that the father is behind the son, but in a very specific way that naturalizes the scene, as if the whole poster is a photograph taken of both the father and son in such a position.

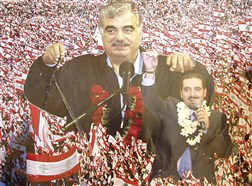

I will now analyze posters that are purely part of Saaddine Al Hariri's election campaign. In the poster with crowds of people demonstrating (fig. 10) the implicit message is 'zay ma hiyyeh' ('as it is'), a statement that has become a recognized part of both the father and son's political campaigns. Before every election, Rafik al Hariri used to address his supporters telling them what they should do on Election Day. He ended this speech by asking them to vote for the whole list of names of his political bloc. This speech became a tradition that was passed on to the son as well throughout his campaign. What is different in this poster is the representation of Rafik al Hariri in his everyday clothes. Election day is one of the rare times when he used to be seen in such clothes. He and his son are superimposed to become part of the crowd, and one of the messages is to show the number of followers the Hariri family have. This support is also reinforced through the red roses and white gardenia around their necks, given to them by their many supporters. The white around Saad's neck could symbolize hope and peace, whereas the red around the father's neck may be a symbolic reminder of his blood and his martyrdom. The Lebanese flag is the most dominant element in the photograph, in addition to some slogans such as '100% Lebanese', with no presence of any of the various political party flags. All these elements make it clear that this is a crowd of March 14 supporters, taken at a demonstration in Martyrs' Square calling for the ousting of Syrian troops and political involvement in the country.

Concerning the scale of elements in this poster, the father and son are humungous in comparison to the crowd of people. They are the leaders addressing their people, but at the same time they are coming out of the crowd, as if part of it. All of this is a reminder to the people that the son is here to continue the journey that his father started. This message is reinforced through the identical hand gesture that both are using.

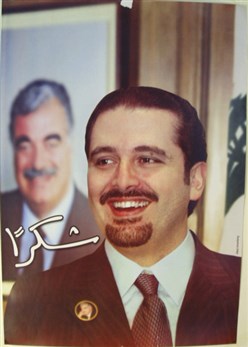

Another poster that communicates the desire of the leader to merge with the people is one that was released directly after the election results. This poster depicts the son with a framed photo of his father behind him, and both are smiling (fig. 11). This is the first poster where the new leader is depicted as happy since his father's death. He has won the elections and is now thanking his people and showing them the happiness that this success has brought to him. It is accompanied by a handwritten "thank you", which shortens the distance between the leader and the people, addressing his supporters in a more personal, informal way.

It is here where we begin to see the father being pushed into the background, as can be seen in the blurriness of his framed image. Now he is within a photo frame, looking on and enjoying his son's success. He is no longer present in person and as strong as he was in the previous posters. In those posters, the son was not yet a strong figure, and he needed his father's presence and support in order to succeed. However, once the Election results secured the victory of his son's political bloc in parliament, the father's role is not so important, and he becomes a framed photograph; still watching, but with a significantly diminished presence.

I would like to end my analysis of the Hariri posters with Saaddine Al Hariri's photograph standing in his elegant suit, looking sideways with one hand in his pocket and the other holding an expensive phone (fig. 7). This setting is so familiar that one might mistake it for an advertisement for fancy men's suits, such as Hugo Boss. The medium that is used for Hariri's posters resembles upscale male-fashion photography. All this adds to the overall image of the Hariri family as successful businessmen, reinforced through these posters and photographs.

The differences in the visual portrayal of the Jomblat and Hariri leaders is certainly due in part to the time gap that separated the two historical periods. Nevertheless, each medium reflects and adds to the image that is being constructed around the two families. Despite these differences, an important common element in both families' posters is never mentioning the name of the leader on any poster produced, whether it is an abstraction of the leader or a photograph. Image here becomes symbolic, just like any word that represents a specific meaning naturally associated with it. People don't need to be told who is the person represented in a poster or photograph; he has become a symbol that is recognized by everyone.

Lastly are the linguistic elements, which are not always present in all posters. For example, the Hariri posters rarely have written components, assuming the photographs speak for themselves. Facial expressions, backgrounds, gestures, etcetera, all combine to form one message, which the propagandist thinks does not require re-emphasis through words. As for Jomblat posters, slogans are often included, (ex: "a promise is a promise") to add another layer of meaning to the visual message. This clear difference tells us about the approach of the two different political climates; where the more recent climate puts less emphasis on verbal rhetoric and pays more attention to image-based rhetoric.

In conclusion, we saw two distinct types of political propaganda where the death of the father/leader was used as a powerful base to promote and shed light on a future son/leader. Appealing to the emotions of the audience plays a very important role in such cases, especially when a loved and popular leader is assassinated. Propagandists use this loyalty to tap into people's emotions, and move on to deliver the message they want to convey. It is true that the main message in the cases of both Jomblat and Hariri was to give legitimacy to the son. But the different circumstances of inheritance were blatantly obvious in the respective posters of the two leaders. As a result, an entire image was created around each family. The image of Hariri the modern businessman was based on the idea of inherited wealth and power. Alternatively Jomblat's image of inherited leadership was based on traditional feudal politics though populist in appeal.[10]

It is normal for such posters to be understood by the public as one overall message. These posters have become such a natural part of our daily environment that we do not think of questioning them. But if deconstructed into their constituent elements, where each element is analyzed alone and then re-examined in relation to the others and how they form the overall message, a much more complex meaning emerges. Whether it was in 1977 in the middle of the war, or during more stable times decades later, we can notice a similar process of inheritance of leadership. While Jomblat and Hariri represent two totally different categories of 'za'im,' and their posters reflect many of these differences, the process of naturalizing and paving the way for the passing of leadership from father to son is almost the same.

Notes

* This essay was originally written for the Signs of Conflict course at the American University of Beirut in the Spring semester of 2005.

[1] Jomblat, I Speak for Lebanon.

[2] Al Rafik Kamal Jomblat, Tarikh Min Tarikh, Beirut: Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation. Television series.

[3] Al Rafik Kamal Jomblat, Tarikh Min Tarikh, Beirut: Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation. Television series.

[4] Jomblat, I Speak for Lebanon, 41.

[5] Khaled Altaki and Thomas Schellen, Hariri A Phenomenon, (Beirut: KIO Publishers, 2005), 17-19.

[6] Altaki and Schellen, Hariri A Phenomenon, 17-19.

[7] Altaki and Schellen, Hariri A Phenomenon, 17-19.

[8] Altaki and Schellen, Hariri A Phenomenon, 42.

[9]> Altaki and Schellen, Hariri A Phenomenon, 49.

[10] As'ad Abu Khalil, "Druze, Sunni and Shiite Political Leadership in Present-Day Lebanon," Arab Studies Quarterly 7, no. 4 (1985).

Bibliography

Abu Khalil, As'ad. "Druze, Sunni and Shiite Political Leadership in Present-Day Lebanon." Arab Studies Quarterly 7, no. 4 (1985): 28-58.

Al Rafik Kamal Jomblat, Tarikh Min Tarikh. Beirut: Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation. Television series.

Altaki, Khaled, and Thomas Schellen. Hariri A Phenomenon. Beirut: KIO Publishers, 2005.

Barthes, Roland. "The Rhetoric of the Image." In Image, Music, Text, edited and translated by Stephen Heath, 32-51. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977.

Dajani, Nabil. Disoriented Media in a Fragmented Society. Beirut: American University of Beirut, 1992.

Harik, Judith. The Public and Social Services of the Lebanese Militias. Oxford: Center for Lebanese Studies, 1994.

Jomblat, Kamal. I Speak for Lebanon. London: Zed press, 1982.

Shararah, Waddah. Hurub il Istitba' (Wars of Followership). Beirut: Dar al Tali'ah, 1979.

Thiban, Sami. Al Haraka al Wataniyya al Lobnaniyya. Beirut: Dar al Masira.