Chapter 1

Agents, Aesthetic Genres and Localities

Unlike various aesthetic genres of political posters in world history - Soviet socialist realism, Nazi realism, Cuban solidarity posters, among others - the political posters of Lebanon's civil war did not make up a uniform national aesthetic genre that is specific to the country and the event of the war. An evident factor is the absence of a single hegemonic voice and state media apparatus in which a unified political poster genre could develop - a typical scenario to post-revolutions and state warfare in which known poster styles have emerged. The civil war in Lebanon witnessed instead multiple factions of distinct political communities with their respective parties acting as each community's official voice and operating their own media offices. The parties' different ideological frameworks and alliance to diverse regional and international political powers have materialized in equally disparate graphic vocabularies. The lack of a single hegemonic centre and consensus over a national identity can be traced at the level of the aesthetic fragmentation of the posters. For the aesthetic component of the poster is a code that forms an inseparable part of the overall message discourse.

Besides the fact that we cannot claim a unified political poster genre intrinsic to Lebanon, it is also misleading to assume that the civil war constituted a break with pre-existing aesthetic practices in the local visual culture or initiated new aesthetic movements. This, of course, does not overlook the fact that political posters were significantly abundant between 1975 and 1990 and that the discourses and iconography were undeniably linked to the rising conflicts and construction of political identities (as will be discussed at length in the next four chapters). At the level of the aesthetic form however, the political posters have in fact built on the different contemporary visual practices in Lebanon and the Arab region, ranging from Modern painting, book illustration and political cartoon to popular film hoardings. These practices have set the predominant aesthetic typologies of Lebanon's civil war posters. So the posters are aesthetically informed by the professional practices of their authors, as well as networks of collaboration and political alliances between Lebanese political factions and other regional and international political movements.

This chapter provides an analytic study of the prevailing aesthetic genres of political posters during wartime Lebanon and will be divided accordingly. While identifying the characteristics of each genre, I will be addressing the professional practice and individual aesthetic styles of some key poster authors, their affiliation to a certain political struggle, as well as regional and international aesthetic influences to their poster undertaking. Before moving into the aesthetic genres, I will first begin with addressing the role of media offices in political parties to examine their agency in the production and aesthetic materialization of political posters.

The role of media offices in political parties

The media offices in the majority of Lebanese parties were mostly concerned with the party's publications, newspapers, periodicals and other party literature.[1] The parties did not set up visual arts departments, or engage experts in that area full-time. The media officials of the Lebanese parties were mostly journalists or intellectuals, members of the political bureau, normally eloquent writers, at home with the party's discourse and literature. Nonetheless, their responsibilities involved the issuing of posters among other party publications.[2] All too often, the media official acted as the copywriter, writing the text or slogan, and handled the art direction of the posters. This explains, in part, the abundance of the calligraphy-based posters during the civil war and the primacy of text in political posters in general - politically loaded rhetoric, eloquent slogans, quotations from the party founder or contemporary poets as well as references to classical Arabic poetry.

The calligraphy-centred poster in Lebanon and the Arab world is a continuation of an old practice through new means of production. Words and Arabic calligraphy have historically been engrained in the street culture and architectural landscape of Arab cities. Whether in the form of Koranic verses that ornament the façades of mosques, mansions and symbolic buildings, or in modern times the public banner, yafta,[3] mounted in the streets to voice public political commentary, the calligraphic word has had its symbolic, communicative and aesthetic potency in the public domain. The yafta in the Arab world preceded the poster as a modern means for the public dissemination of political messages, and occupied the streets at moments of popular uprising and political campaigning. Its value lies in the primacy of the word in public expression and in attributing aesthetic quality to calligraphy, which would vary in style and formal complexity according to the type of message. It hence formed an intrinsic component of the street vernacular of major Arab cities since the first decades of the twentieth century. The calligraphic poster in Lebanon followed similar principles to the yafta, in calligraphic style and type of message. In its limited size and large print run, it came to be a commonly adopted poster genre during the civil war, easily and cheaply published by the party.

The process of art direction of posters by media officials involved commissioning specialist calligraphers and illustrators to render their ideas visually, or too often just getting these directly executed at an affiliated printing press. The majority of parties did not own printing presses but instead held close working relationships particularly with those affiliated to the party, near their headquarters, or in the areas they had political and military control over. Some establishments became the 'official' printers of a certain party. Raidy Printing Press, being an established press in the predominantly Christian eastern sector of Beirut and located nearby the Kataeb headquarters, printed most of the Kataeb party and Lebanese Forces publications. On the other hand Techno Press, another major printing establishment, which relocated to west Beirut during the civil war, did work for a variety of leftist parties active in the western sector of the city - the Palestinian organizations, the Progressive Socialist Party and the Lebanese Communist Party. It provided services free of charge for the latter, as the owner of the press and most of its workers were active members of the Lebanese Communist Party.

The posters that the media official executed at the printing press form the larger part of the civil war posters, which were produced under time pressure and conditions of limited communication and mobility during the war. These would usually follow basic layouts and standard templates in their composition, repetitively applied for recurrent subjects. These standardized poster formats were most commonly applied in posters based on portraits of martyrs and political leaders. The central image would be a photographic portrait, accompanied by typical party slogans and related information (see figs in chapters 2 and 4).

Conversely, on special occasions - party anniversary, a political leader's death/assassination or other significant commemorative events - an artist would be called upon to volunteer his/her artwork for a poster. That depended on the party's own network of affiliation with artists in Lebanon and contemporary artists' political commitment, which will be addressed in the following sections.

Political fervour among left-wing Arab artists

The posters of the Palestinian resistance filled the walls of cities in Lebanon from the late 1960s onwards and were a precursor to political posters of the Lebanese civil war. The former presented a model in terms of aesthetic genres, shared revolutionary discourse and iconography pertaining to armed struggle and popular resistance. This was particular to the Lebanese left-wing and Arab nationalist parties, allied with the Palestinian organizations and fighting on the same front. The alliance between the Lebanese National Movement (LNM) and Palestinian organizations forged networks of media and artistic collaboration, whereby a number of artists designed posters for both the Palestinian resistance and the Lebanese parties to which they were affiliated. This makes it difficult to dissociate the aesthetic approaches of Lebanese left-wing political posters from those centred on the Palestinian struggle. In what follows I will discuss the context (political and aesthetic) in which Arab political posters emerged while focusing on examples of artists and posters that directly relate to the Lebanese civil war.

Following the devastating military defeat of Arab states against Israel in 1967, Lebanon among other Arab countries witnessed the rise of Palestinian resistance movements. The struggle for the liberation of a lost homeland that the various movements engaged in was coupled with relentless efforts in organized media activity to advocate the Palestinian cause. The media office of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, based in Beirut, acted as the Unified Information Office and included a fine arts department that catered for the art-related activities of the organization, including the publishing of posters. However it did not hinder poster publishing by other Palestinian organizations and civil movements or by independent Arab and international artists. Posters, among other means, played a key role in awakening or maintaining national identity and mobilizing the youth to actively partake in the resistance, as well as calling for international solidarity with the Palestinian people in their struggle for liberation and social justice.

As the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) relocated from Jordan to Beirut in the early 1970s, it found local support and enthusiasm among the Lebanese left: allied Lebanese political parties, artists and intellectuals, in addition to a fervour among radical youth movements of the time. Meanwhile, Beirut in the sixties was living its heyday as the cosmopolitan centre of the Arab world. The city enchanted businessmen, tourists, artists and intellectuals from the region to partake in its adventure of modernity. This, with a thriving scene in the arts and culture - international music festivals, burgeoning art galleries, venues for alternative theatre productions, in addition to vigorous publishing houses and Arabic book fairs enjoying the intellectual freedom that neighbouring Arab countries at the time lacked - set Beirut in the 1960s as the cultural centre of the Arab world. While the 'Paris of the East' thrilled its dwellers and visitors with a booming economy and assimilation of Western models of consumerism and modern lifestyles, a large segment of the Lebanese population was publicly voicing its economic deprivation and demanding political and social reforms. Describing the rising social movements, strikes and demonstrations that swept the country at the time, Fawwaz Traboulsi notes: 'Much more than a protest movement, it was a radical questioning of Lebanese and Arab societies from a moral and cultural point of view, greatly influenced by the defeat of June 1967, the emergence of the Palestinian resistance and the impact of May 1968 in France.'[4]

The artistic climate in Beirut and other Arab cities, coupled with heightened politicization, created a fertile ground for the development of political posters. Politically engaged artists saw in the poster a public platform to voice their positions and an expansion of their artistic practice from the confines of the galleries to the openness of the city walls. Many prominent Arab artists - Palestinian, Lebanese, Syrian, Iraqi and Egyptian, among others - contributed with great ardency to the design of political posters and advanced distinctive aesthetic standards. Political posters advocating the Palestinian cause have been part of a thriving movement of political engagement through art that called for Arab artists, film-makers and intellectuals' political participation in the socio-political struggles of the region: liberation movements, Arab nationalism, class struggle and opposition to different forms of social injustice.[5] This unprecedented active participation brought esteem to posters as an art form, manifested in institutional support such as international competitions, exhibitions and publications. It started with an exhibition organized by the PLO Unified Information Office with the title International Exhibition for Palestine, held at the Beirut Arab University in March 1978, followed the next year by a second in the same location, called Exhibition of Palestinian Posters 1967-1979.

Among the Arab countries, Iraq had been the forerunner in advancing the poster as a legitimate art form in the 1970s, by issuing state-endorsed poster exhibitions and through the participation in international poster biennales of some of the leading modern Iraqi artists of the period. Among these is Dia' al-Azzawi who besides his participation in the design of posters and organization of exhibitions also wrote a book in 1974, probably the first of its kind in the Arab world, entitled The Art of Posters in Iraq, a study of its beginning and development 1938-1973.[6] The Iraqis continued to be active on that front and organized in 1979 the Baghdad International Poster Exhibition including a juried international poster competition centred on two themes: 'The third-world struggle for liberation' and 'Palestine, a homeland denied'.

In the absence of academic training in graphic design at the time in Lebanon, it was the formally trained artists, mostly renowned ones, who took the lead in the design of political posters. Generally, prominent modern artists in Lebanon contributed mostly to left-wing and Arab nationalist political parties coalescing under the LNM. This was consistent with the movement of political activism among Arab artists in the late 1960s. As addressed above, the political fervour had materialized early on in posters calling for solidarity with the Palestinian cause, which eventually forged the way for artists' engagement in designing political posters during the Lebanese civil war.

The artists' contributions were sporadic and did not form a steady flow of poster production that could get institutionalized into the Lebanese parties' media framework. The poster artwork was mostly on a volunteer basis and came subsidiary to their main artistic practices, which established artists tried to maintain throughout the war. The poster was generally conceived as an act of political struggle and commitment to a cause through art rather than a professional service, as described by many of the artists and media officials. Additionally, as the connections were ruptured between the various Lebanese communities during the war, the contact between artists and parties was not always an easy process. Some artists maintained unofficial affiliations to parties and opted for anonymous poster contributions in order not to jeopardize their social and professional relations. More so, as the party militias got more involved in violent reprisals and confessional hostilities through the unfolding of the war, many artists discontinued their party affiliation.

The left-wing political posters in Lebanon did not hold a unified aesthetic genre. As with the Palestinian posters, each artist contributed with an already established style of his/her own. The artists' posters were aesthetically as diversified as their authors' painterly approaches. The poster was too often conceived as an aesthetically complex painting. Quite typically, a painting or drawing would be made by the artist before it was adapted into a poster, whereby the text would be sidelined to the author's artwork. Essentially, the artists in most part did not really dwell on the design process of a poster but rather offered their artwork to be published in a poster format. Artists developed posters based on their own artistic preoccupations, which in many cases incorporated their political concerns, not only in the subject matter but also at the level of the visual form. These artistic explorations were contemporaneous with a general undercurrent of modern art in the Arab world in search for a relation with its locality and history. The search for identity among Arab modern artists was tightly linked to regional political and cultural factors following the Second World War. With the decline of Western colonial power over the region, strong sentiments of nationalism and quests for cultural identity steered Arab countries and people. In an overview of modern Arab art, Wijdan Ali notes:

It was this cultural reawakening which led to the third stage in the development of contemporary art in the Arab world. This search for national identity was preceded by several decades of stylistic homogeneity, during which Western tradition, rather than experimentation, was the guiding principle. . . . This cultural paradox induced them [the artists] to develop an indigenous art language based on traditional elements of Arabic art - including the arabesque, two-dimensional Islamic miniature painting, Arabic calligraphy, Eastern church icons, archaeological figures, ancient and modern legends, folk tales, Arabic literature and social and political events - but employing contemporary media and modes of interpretation.[7]

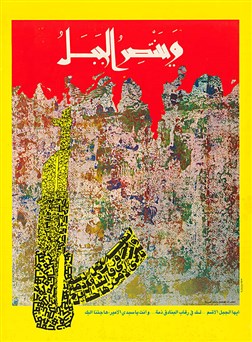

Such artistic explorations are particularly pronounced in the contributions of Arab modern artists to the posters centred on the Palestinian struggle. This practice resonated in a number of the Lebanese war posters, in which local artists transposed their artwork from the canvas to the poster. An initial example is the artist Omran Kaysi (1943-) of Iraqi origin. Kaysi, who lived in Lebanon, was inspired by the Arabic calligraphy movement that emerged in Iraqi modern visual arts during the early 1970s and stimulated many other contemporary Arab artists. The formal language is premised on political consciousness of one's cultural position as well as spiritual groundings inspired by the aesthetic heritage of calligraphic gestures and the geometry of arabesque. Kaysi worked on posters during the early and mid-1980s that supported the national resistance against Israeli occupation, particularly centred on the solidarity with the southern coastal city of Saida (fig. 1 and fig. 2). Some of his posters took the form of abstract graphic explorations, featuring elaborate Arabic calligraphy and arabesque motifs adapted from the artist's own paintings and drawings.

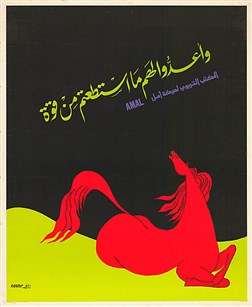

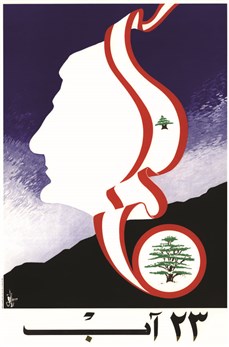

In a different visual vocabulary, yet equally pertaining to local cultural heritage, the renowned Lebanese artist Rafic Charaf (1932-2003) also adapted his painting subjects into posters. He transposed mythical icons of Arab heroism from past times, found in old Arab poetry and folk tales, to a present moment of political struggle. His early political posters addressed the Arab struggle with Israel and praised the Palestinian resistance. By the mid-1980s, Charaf's posters were centred on the Lebanese national resistance in its fight to end Israeli occupation (fig. 3).

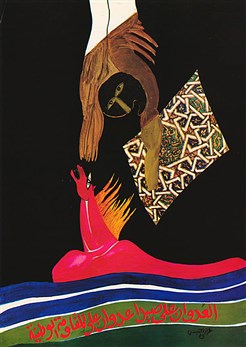

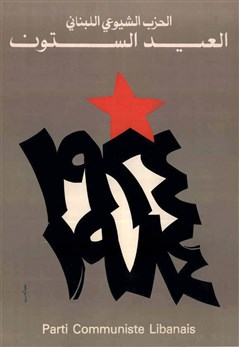

Paul Guiragossian (1926-93), another highly acclaimed Lebanese artist, had already been designing posters for some of the leading cultural events since the late 1960s. His poster contributions took a political turn during the war as he volunteered his artwork for the Lebanese Communist Party (LCP) and other civil organizations supporting the national resistance to Israeli occupation (fig. 4, fig. 5). Guiragossian's poster compositions hold direct symbolism and resemble drawings in an artist's sketchbook. China ink and red wash paint dynamic human figures, silhouettes of anonymous heroes and workers in struggle for liberation.

Such examples of artist contributions in posters hold more the aesthetic qualities of a painting than those of a poster. The message is visually complex and highly interpretive, unlike a promotional poster designed to communicate swiftly and efficiently. Nevertheless, they reflect their authors' sense of belonging to a political struggle. Yet the authors' artistic practices continued to be their primary occupations, with occasional escapades from the canvas to the printed poster. This is often the case when the artist offers a painted portrait in tribute to an acclaimed political leader. Portraits in such posters reflected the artists' modern formal expression and sophisticated aesthetic representation. Such portrait-centred posters were unconventional with respect to the prevailing popular romantic realism or photographic portraiture of acclaimed leaders and election candidates.

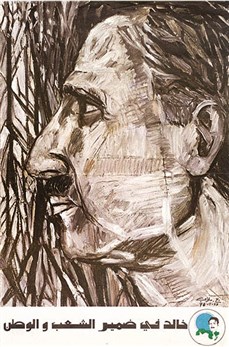

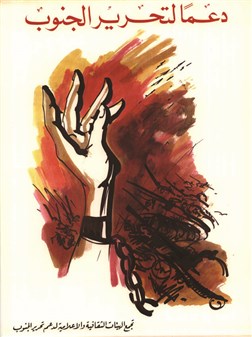

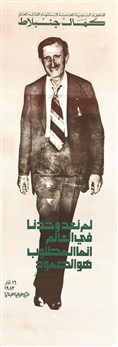

This type of poster is exemplified by the abundant group centred on the commemoration of Kamal Jumblatt, founder of the Progressive Socialist Party and leader of the Lebanese National Movement, following his assassination in 1977. A number of renowned artists, namely Imad Abou Ajram (1940-), Wahib Bteddini (1929-), Jamil Molaeb (1948-), Aref el-Rayess (1928-2005) and Moussa Tiba (1939-), participated in paying tribute to the fallen leader (fig. 6). Resistance to Israeli occupation of South Lebanon has equally been the subject of many posters by prominent local artists. A number of these posters were issued by civil organizations, such as the Cultural Council for South Lebanon. The council grouped a number of Lebanese left-wing intellectuals and organized yearly cultural activities, exhibitions, conferences and publications, centred on the themes of national resistance and desires for liberation. (fig. 7 and fig. 8)

Artists take on graphic design

Alternatively, a number of artists engaged in the poster design process as a total creative endeavour. In particular, those who in parallel to their artistic practice earned a professional experience in graphic design and illustration ultimately became familiar with the poster's functional requirements. They employed more simplified illustrations and planned graphic compositions, including photographic montages, which integrated the typographic/calligraphic message into the overall poster layout. While responding to modern currents of visual expression and the functional requirements of a poster, the artists did not fully share the aesthetic of an international design modernism that overwhelmed graphic design in the West during the 1960s. That movement, based on premises of functionalism and quests for a universal language of form, favoured a rational approach to graphic design over the subjective expression of the artist. At variance with Western approaches to modern design, the Arab artists brought to the poster their own distinctive artistic styles and cultural localities.

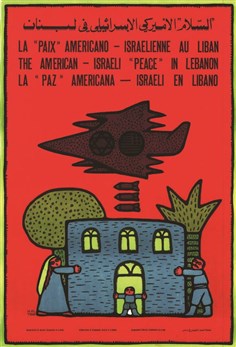

The concern for a culturally grounded and simplified pictorial approach is most common among the Palestinian posters, exemplified by the works of Burhan Karkutli (Syria, 1931-2000) and Helmi el-Touni (Egypt, 1934-). These, among a number of Arab artists, including Mohieddin Ellabbad (Egypt, 1940-2010), were part of an emerging collective in the early 1970s concerned with advancing illustrated Arabic books. Dar al-Fata al-Arabi, a publishing house specialized in Arabic children's books founded in 1974 in Beirut, acted as a pivotal point in modern illustrated Arabic books and a platform that grouped a number of creative talents in the Arab world. It offered a space to address contemporary issues of local social and political significance through popular means of graphic communication. A number of Dar al-Fata al-Arabi's publications were centred on the Palestinian cause and advocated the necessity of struggle to reclaim a lost homeland to a young readership.

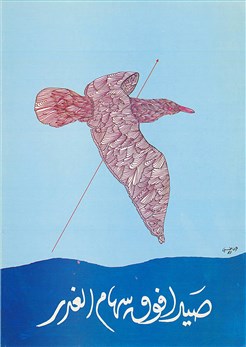

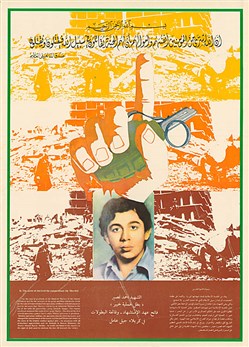

Illustrations of such publications were often issued as posters. Among these are the works of Helmi el-Touni, who lived in Beirut from 1973 to 1983. As a politically engaged artist el-Touni was banned from practice in Egypt during Sadat's reign. He therefore moved to Beirut, where he worked as illustrator and designer for local publishing houses and cultural institutions. During his residency in Lebanon he designed posters for different political and civil rights organizations in addition to Lebanese left-wing and Arab nationalist parties. He particularly focused on the subject of popular resistance, where he always portrayed women as active social agents (fig. 9). Helmi el-Touni has developed a formal language of his own inspired by the different visual manifestations of local popular culture from contemporary vernacular mural paintings in Egypt to indigenous North African tattoos, and the heritage of Islamic miniature painting. His illustrations are ripe with popular symbols and representations of hopeful imaginary realms, drawn in flattened compositions and simplified shapes defined by warm and bright colours.

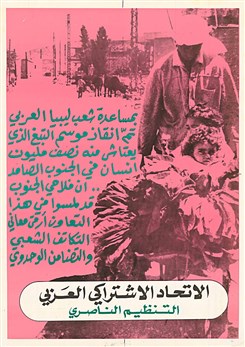

The Syrian artist Youssef Abdelkeh (1951-), exiled from Syria, lived in Beirut for a short while before settling in Paris. Abdelkeh has equally engaged in children's book illustration with Dar al-Fata al-Arabi and poster design in parallel to his artwork. His main poster contributions, mostly to the Lebanese Communist Party to which he was affiliated, held straightforward graphic compositions while being aesthetically intriguing (fig. 10). The LCP, in fact, had the most varied poster contributions from prominent Lebanese artists: Samir Khaddage (1938-), Seta Manoukian (1954-), Emil Menhem (1951-) and Hussein Yaghi (1950-), in addition to the above-discussed posters of Guiragossian. These artists had already been involved in designing posters for Palestinian organizations and had formed among themselves a collaborative workspace. Among them, Emil Menhem has gained more interest in graphic design through his political poster experience and ultimately embraced the profession. Menhem also designed his own Arabic typefaces; he explains that his interest in Arabic type began while designing posters as he felt the need to create the appropriate modern Arabic type for each poster composition (fig. 11). Kameel Hawa is another similar case of an artist who shifted his career towards graphic design stimulated by his practice of designing political posters in the early phase of the war.[8] Hawa's political inclinations, on the other hand, were Arab nationalist, which brought him to design a significant number of posters for the Socialist Arab Union in Lebanon mostly centred on popular struggle. His posters vary between elaborate drawings and modern pictorial representations where his own Arabic hand lettering forms a dynamic integrated layer of the graphic composition. (fig. 12)

Networks of solidarity from Cuba to Beirut and back

The diverse posters discussed so far reveal the identifiable style and cultural specificity of the artist, responding to a general undercurrent of modern art in the Arab world. Nonetheless, a number of Arab political posters corresponded with the aesthetic genres of other contemporary anti-imperialist struggle and revolutionary movements' posters, particularly the solidarity posters issued by the Cuban-based OSPAAAL (Organization in Solidarity with the People of Africa, Asia, and Latin America). The poster compositions are essentially comparable in terms of the 1960s Pop aesthetics, pictorial abstraction and vigorous colours.[9] In fact, the OSPAAAL posters were sent to Lebanon in coordination with the various Palestinian organizations and allied left-wing Lebanese parties. A number of the OSPAAAL posters were centred on the subjects of resistance and liberation in different Arab countries, among these the Palestinian resistance and Lebanon under Israeli occupation. In a less abundant stream, the Palestinian organizations published a few posters in solidarity with revolutionary causes in Latin American countries. The Cuban artist Olivio Martinez narrates with emotive words this period's thrust of solidarity in political struggle:

On many occasions, delegates of movements from three continents came and told me of their joy at the response to a specific poster among their particular fighting force and nation, which adopted it as if it were their own. These times are among my greatest professional moments of happiness. . . . I'm referring to my 1972 poster for solidarity with the Palestinian people. This image was so heartfelt for them that they used it on the cover of an Al Fateh magazine . . . as their identifying logo for the movement's editorials in the publication. They admired it so much that on one of Yasser Arafat's visits to Cuba, Fidel presented him with the original artwork.[10]

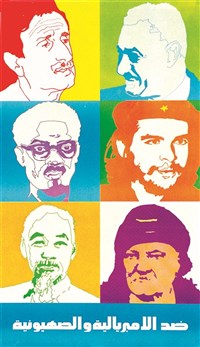

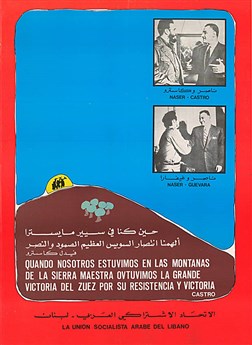

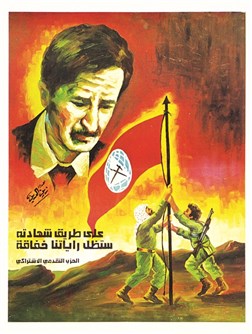

Not only did the visual language of a number of Palestinian resistance posters respond to the Cuban graphics of the time, they are equally homologous in the iconographic representations pertaining to armed struggle, popular resistance and revolutionary discourse - heroic guerrilla, weapons (AK-47), clenched fist and depictions of imperial powers. This aesthetic, which was equally prevalent among the Lebanese posters, held the connotations of leftist politics of that era. In Lebanon, it meant not only Marxist politics but signified other forms of anti-imperialist and anti-Zionist struggles, which articulated revolutionary liberation struggles with Arab unionist quests. Arab nationalist parties therefore adopted this graphic language as much as parties with Marxist orientations (fig. 13). The networks of aesthetic exchange were brought by the political alliances between Cuba and revolutionary movements in Arab countries. The Socialist Arab Union in Lebanon, for instance, sent student delegates from the party to a Youth Congress in Cuba held in 1981. The designer Kameel Hawa produced a multilingual poster for that occasion, highlighting Cuba's support and the relation of Abd-el-Nasser with both Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. The delegates from Lebanon also organized for that purpose an exhibition of posters in Cuba with the title Exhibition of posters in support of the Palestinian revolution and the Arab identity of Lebanon (fig. 14 and fig. 15).

Political cartoon and burlesque satire

Another aesthetic genre that typifies the political posters of the Lebanese civil war is characterized by the numerous contributions of political cartoonists to poster design. This typology of posters is probably the most evident. Political cartoon has figured in the Arab press since the early twentieth century. It has gained popularity over the years and established itself as a legitimate creative practice that combines artistic skills and wit with expression, aimed towards a mass audience. It is unsurprising that such an aesthetic genre would be extended to political posters. These hold more direct political expression of the subject through a compositional arrangement heavy on symbolic signs. In turn, the signs are materialized by simplified figurative drawings relying on conventional political codes and literal visualizations of collective imaginings particular to the distinct communities being addressed. The drawings, marked by the signature style of the various authors, employ methods of exaggeration that highlight the political message and the subject's distinguishing features, ranging from heroic praise and glorification to burlesque caricature and political satire. While a number of local amateur cartoonists have been active on that front, I will exemplify my study of this poster genre with the works of two prominent Lebanese political cartoonists, Pierre Sadek and Nabil Kdouh, who produced a substantial number of posters during the war.

Pierre Sadek is a leading figure in political cartoon in Lebanon; he obtained numerous awards and international recognition for his political satire in the daily press. He published a book in 1977, comprising caricatures with overt commentary on the civil war politics, titled Kulluna 'al watan (All [fighting] over the Nation), a parody of the national anthem Kulluna lil watan ('All for the Nation'). Sadek, a vehement advocate of Lebanese nationalism, has volunteered his skills for numerous posters promoting the Lebanese army. He also contributed a considerable number of posters for the Lebanese Kataeb Party and its affiliated military organization, the Lebanese Forces (LF) (fig. 16 and fig. 17). These were particularly abundant after the assassination in 1982 of Bashir Gemayel, military commander of the Lebanese Front and short-lived president of the Lebanese Republic, and centred on the commemoration of the lost leader. Sadek describes his political posters as a tribute to a leader he greatly admired, 'whose vision of Lebanon coincides with his own aspirations'.[11] In confirmation of his admiration and grief over the lost leader, he also published a drawing book in 1983 dedicated to the memory of Bashir Gemayel.

Besides posters, Pierre Sadek participated in other mass-media establishments of the LF during the 1980s. He illustrated covers for the magazine al-Massira, in addition to drawing daily caricatures for the television station LBC (Lebanese Broadcast Corporation). His signature style in political cartoons as well as illustrations is quickly discernable and can be traced in his poster work. Simplified forms and silhouetted shapes or portraits make up the central figures and symbols of his compositions. His black ink drawings are mostly rendered in vigorous cross-hatchings and hence create an intricate contrast between shaded areas and lit ones. The graphic elements are composed in a playful relation between positive and negative forms, designed against a flat minimalist background. These formal tactics added to the straightforwardness of the symbolic representations in his posters, create an eye-catching image that's hard to miss and require very little text to anchor the message, an approach typical to political cartoon.

Aside from Sadek, very few professionals contributed to the posters of the Lebanese Front parties. As the collection of political posters reveals and as confirmed by political officials in those parties, the production of posters within the Lebanese Front was relatively limited in comparison to the abundance of posters issued by their adversaries. That was due to several reasons that will be addressed towards the end of this chapter. Amateur illustrators drew the relatively few posters issued during the 1970s, which makes the political cartoon typology dominant among the Lebanese Front posters of that period, often with burlesque exaggeration and naive symbolism lacking the subtleties of Pierre Sadek.

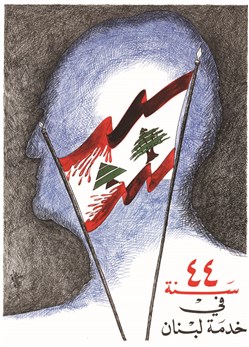

Nabil Kdouh is another professionally trained political cartoonist who executed a substantial number of posters during the civil war period. He, on the other hand, contributed mostly to factions within the Lebanese National Movement. His political cartoon for the LNM newspaper al-Watan has prompted various parties of the LNM - the Progressive Socialist Party, the Syrian Social Nationalist Party and the Independent Nasserist Movement (Murabitun) - to solicit his illustrations for their magazine covers as well as their posters. Kdouh claims he had no political engagement, nor adherence to any party; this allowed him to take commissions from parties with diverging ideological frameworks. Illustration became his profession, he says. Nevertheless, being originally from the south of Lebanon, he became more inclined in the 1980s to work on illustrations representing national belonging and popular resistance to occupation. Since then, Nabil Kdouh mostly designed posters for the Amal movement, while still maintaining that he never adhered to the party's political activities. His affiliation, as he explains, was based on shared belonging and his admiration for the movement's leader.[12]

Kdouh closely collaborated with Amal's media office to devise each poster's message; the media director would develop the text, which in turn would inspire Kdouh to illustrate. Relying on freehand ink drawing and aquarelle tints, his illustrations are rich with details, resulting in posters that appear like visually recounted narratives resembling popular comics. The purpose, according to Kdouh, is to convey the poster message through direct visual representations, which can be easily accessible to a large audience comprising rural areas that hold a high rate of illiteracy (fig. 18). Through his poster drawings, Nabil Kdouh has moved from satire to expressive illustrations. He eventually got more inclined to children's illustrations, which became his profession, and withdrew entirely from political posters towards the end of the war.

Popular realism and politico-religious imaginings

As icons of political leadership gained more intensity during the civil war, leaders' portraits pervaded the public space. Aside from posters, immense painted portraits governed over symbolic locations within communities' territorial claims. The phenomenon was amplified in the 1980s, as the country witnessed further segregation according to tight sectarian divides and battles over territories. Specialized promotional hoardings painters were solicited to execute the mega-scale portraits of political figures. Muhammad Moussalli, a self-trained painter who began his career in the 1960s mainly doing portraits of electoral candidates and advertisements for multinational commercial brands, had during the war a long waiting list of commissions from various political factions. Moussalli recounts how he was esteemed by his 'high-positioned clients' and was often called 'the king of portraiture'.[13] He explains that the artistry lay not only in getting the portrait as close as possible to reality but in rendering the figure charismatic and more appealing than reality. Moussalli would produce a series of up to 70–100 similar hand-painted portraits for the same political figure during the war period, so as to fulfil manually the function of a mechanically mass-produced poster.[14]

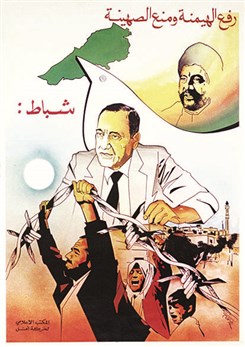

Additionally, painters of Arab film hoardings designed political posters in the same romanticized style normally assigned for the promotion of films. One example is Mahmoud Zeineddine; he extended his painting skills to printed posters, chiefly for the Progressive Socialist Party to which he ascribed his Druze belonging. The aesthetics of popular realism and romanticism associated with the promotion of films and star actors was transposed, in Zeineddine's posters, to portraits of mythical leaders and scenes of military heroism. (fig. 19)

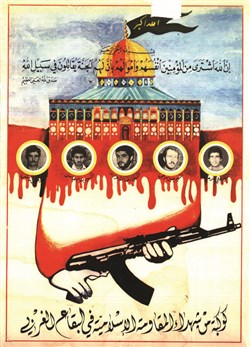

The romanticized version of realist painting was prevalent amongst the emerging Islamic movements of the mid-1980s. It is particularly abundant in posters honouring the fallen martyrs of the Islamic Resistance, the military wing of Hizbullah. Throughout the 1980s Hizbullah's media office would have a portrait painted in oils for each martyr, which would be offered to the martyr's family and ultimately used for the poster. The compositions featured idyllic portraits of the deceased and narratives surrounding the religious sanctity in which the struggle and martyrdom were inscribed (see chapter 4). The posters present pseudo-realist painted compositions of imaginative settings derived from a repertoire of religious representations in Shi'ite history and mythology. That kind of aesthetics offers the possibility to render what is collectively imagined, in terms of religious texts and symbols, into realist yet simultaneously mythical images with popular appeal (fig. 20).

The case of Hizbullah's media office presents an exception to the prevailing models of poster production by political parties discussed above. After informally relying on networks of affiliated artists and resources, by 1985 Hizbullah had a full-fledged set-up for artistic production within its media structure. The party provided a collective workspace, equipped with the needed tools and resources, including a library of references on political art and posters. The work process on the posters was mostly collaborative, involving the different skills of experts engaged in the workshop team. An illustrator/designer handled the conception of the poster and acted as the art director, a painter worked on the portraits, a calligrapher attended to the titling and Koranic inscriptions and a technician handled the preparation for printing. The painters and calligraphers were also involved in other media projects besides posters, such as mural paintings, public hoardings and banners - yafta. The specialized members were mostly adherents to the party; they shared its ideology and religious convictions and hence operated from within the party's discourse. This facilitated an autonomous process of communication and message encoding of the posters by the team members without the dictation of the political bureau, as one member of the design team describes. Muhammad Ismail joined Hizbullah's media office in 1984 and became a leading designer at the workshop until 1994.[15] Ismail studied Fine Arts at the Lebanese University and practised illustration and political cartoon while he held a job at a printing press before he joined the office and helped in establishing it. His artistic inclination and skills in drawing in addition to his knowledge of printing, as he explains, aided him in the graphic design process.

Hizbullah's posters in the beginning were based on a compounding of previous experiences in political posters: socialist realism, the Palestinian resistance and the Iranian Revolution posters. As a resistance movement against Israeli occupation, Hizbullah shared with these the iconography of subversion of imperialist powers and armed struggle for national liberation. Hizbullah's members had in fact been previously engaged with leftist resistance movements, Palestinian and Lebanese parties, and in most part belonged to the Shi'ite-based Amal movement. The Iranian poster model was most useful since it imbued the anti-imperialist struggle with a politico-religious discourse that is pertinent to Hizbullah and familiar to its Shi'ite community. The Shi'ite community particularly originating from South Lebanon and the Bekaa valley, which makes up Hizbullah's adherents, in fact shared with Iran a history of cultural and religious practices and symbolic representations pertaining to Shi'ism.

As will be discussed in the following chapters, the shared Shi'ite politico-religious discourse, institutionalized through the building of the Islamic Republic of Iran,[16] facilitated transposing the iconography and aesthetics of Iranian posters and adapting them into the Lebanese context. The Islamic Republic, in its pan-Islamic Shi'ite framework, has provided Hizbullah with religious and political guidance through the party's pledged allegiance to Wilayat al-Faqih (the guardianship of the jurisprudent) under the leadership of Khomeini and his successor Khamini'i.[17] Concurrently, Iran has supplied the party with resources and support that enabled the establishment and continued institutional development of the political party and its paramilitary resistance to the Israeli occupation of South Lebanon. Among these resources were also Iranian methods of modern political art. The members of the media office at Hizbullah received training in artistic skills and poster design from Iranian artists who came to Lebanon for short workshops in the early period of the party's establishment. During their short residency in Lebanon, these Iranian artists designed some of the early posters produced between 1983 and 1985, including Hizbullah's logo, which is based on that of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards (Pasderan).

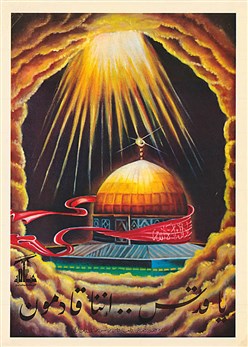

Likewise, some of Hizbullah's early posters make use not only of the iconography and aesthetic genre but also of the same drawings present in Iranian posters. A recurrent example is the colourful illustration of the religious shrine and pan-Islamic symbol of Jerusalem the Dome of the Rock (fig. 21; see chapter 3). In fact the symbol had been fairly well known to a Lebanese audience familiar with the Palestinian liberation movement. Chelkowski and Dabashi, in their book Staging a Revolution: The Art of Persuasion in the Islamic Republic of Iran, claim that the Iranian artists had originally been influenced by Palestinian iconography on this matter through an exhibition of Palestinian political art, brought from Beirut and held in Tehran in 1979.[18] This particular colourful drawing of the Dome of the Rock had in fact been originally painted by the Egyptian illustrator Helmi el-Touni. It features on a poster issued in the 1970s by the Beirut-based publishing house Dar al-Fata al-Arabi. The icon of the Dome of the Rock had thus made quite a journey before it found itself back on the streets of Beirut in the mid-1980s through Hizbullah's posters.

Beyond the particularities of the overtly religious rhetoric of Hizbullah's posters, their aesthetic vocabulary does not constitute a unified typology that can be distinguished from other aesthetic practices of political posters of the Lebanese civil war. Besides the religiously inscribed romanticized painting, Hizbullah's posters often resorted to modern means of design - abstract graphic representations, and montage of photography with illustration - evident in the work of Muhammad Ismail. The eclectic character of Hizbullah's posters corresponds to the articulated structure of their politico-religious discourse as an Islamic Resistance in Lebanon. It is also analogous to the hybrid aesthetics of the Iranian experience, which articulated codes of revolutionary struggle with religious signs of Shi'ite collective imaginary (fig. 22).

Concluding remarks

As the war persisted over 16 years, internal hostilities were aggravated. The decline of basic premises of humanity, rise to power of warlords and militia hegemony, combined with the economic breakdown of the country and the emotional loss that the Lebanese have suffered, ultimately reflected back on the quality of posters. Needless to say, the parties' growing military pursuits throughout the war evidently lowered their attention to the aesthetic quality of posters. Posters became a symbolic means to assert a party's military hegemony over an area; for that purpose, the party's logo and leader's portrait sufficed to symbolically mark the claimed territories.

Artists mostly on the left side of the local politics, who were taken by the fervour of progressive projects and revolutionary causes of the 1960s and 70s, withdrew from their activism as the struggle diverged from its initial reformist goals and crept along narrow confessional lines and into irrational violence. The networks of artistic collaboration that were instated by the alliance of Lebanese parties with Palestinian organizations were severed by the Israeli invasion and the subsequent withdrawal of the PLO from Beirut in 1982. With the exception of efforts put into posters supporting the national resistance to Israeli occupation during the 1980s, the utopian fervour of the previous decades was followed by a decreased interest in political participation and a general sense of distrust. It left the majority of poster design in the hands of media officials, who kept on reproducing the same template formats for most of the posters issued by the party.

On the other hand the opposing camp, the Lebanese Front, had, to begin with, very few contributions from professionals. Compared to their adversaries, the parties that formed the Lebanese Front produced relatively very few posters. Besides Pierre Sadek's engagement with the Kataeb party and the Lebanese Forces, there were hardly any other prominent artists or professionals contributing to their poster production. There are many reasons to explain this. First of all, as I have already addressed, the artists' abundant poster contributions on the left had begun before the war with the Palestinian resistance and coincided with a movement of political engagement among Arab artists with current regional political struggles. These surpassed the specificity of Lebanon and encompassed the Arab-Israeli conflict as well as progressive socio-political struggles. Such sentiments were not shared among the adherents to the Lebanese Front. In fact they were contested by strong affirmations of Lebanese nationalism, as opposed to an Arab one, in addition to right-wing conservatism pronounced by the parties forming the Lebanese Front. Thus the poster practice as a form of artistic political engagement and tool for struggle was a phenomenon particularly tied to left-wing politics and historically linked with revolutionary ideals, from the Bolshevik poster to the Cuban solidarity posters and contemporaneous protest movements.

A second reason is that the Palestinian organizations, based on their own rich experience in the production of posters and through their alliance with the left-wing parties, provided the latter with a creative framework in which the design of political posters could flourish. They equally supplied their allied Lebanese parties with the needed material and human resources for the production of posters.

A third reason is more speculative. It relates to the geopolitics of the war and the nature of the poster as medium of dissemination within the public space. The media offices of the various parties held networks of poster distribution within their own areas of political control. The posters in that sense also acted as a symbolic affirmation of a party's hegemony over a certain territory. The western sector of Beirut was shared as a territorial space among many political parties, which formed, in the 1970s through the early 1980s, the combined forces of the Palestinian organizations and the Lebanese National Movement. It eventually witnessed, in the mid-1980s, the rise of the Islamic Resistance amidst other secular parties which formed the National Resistance Front against Israeli occupation. Aside from rural areas, whose territories were clearly demarcated, west Beirut was a contested terrain of multiple hegemonic articulations by the various parties that fought to maintain their territorial control. This had resulted in multiplied efforts in the production of posters among the different parties supposedly belonging to the same camp. In consequence, central locations in west Beirut witnessed a sort of symbolic competition of politically diverse posters. Media officials recount how posters they put on walls would often be covered the next day by other posters from a different party.

Such a symbolic battle and race in poster production was not practised in the eastern sector of Beirut. To start with, the Lebanese Front included fewer parties than the opposing camp. Additionally, from 1976 the small military groupings dismembered to join the Lebanese Forces commanded by Bashir Gemayel, who by 1980 unified all contingent parties of the front under his command. The unchallenged hegemony of the Lebanese Forces over the Christian eastern sector of Beirut did not lead to the competition and heavy production of posters among parties that west Beirut experienced. In the mid-80s, the Lebanese Forces invested in television broadcast and periodical publication as overreaching mass media and declined their poster activities. The later political discords and battles in the so-called 'Christian territories' between 1989 and 1990 were pronounced instead through these mass media.

Notes

[1] Some parties ran their own radio broadcast station and a few established a television station in the 1980s. These broadcast media had their own institutional setting separate from the party's media office.

[2] The account is based on interviews held with party media officials and poster designers between 2005 and 2006.

[3] The calligraphic banner, yafta, is a hand-painted message on a large cloth 5 to 8 metres wide, which would be either fixed within a street or carried by hand by wooden sticks on both ends during a public march.

[4] Traboulsi, Fawwaz, A History of Modern Lebanon (London: Pluto Press, 2007), p. 169.

[5] See Rabi'i, Shawkat al-, al-Fan al-Tashkili fi al-Fikr al-Arabi al-Thawri (Art in Arab Revolutionary Thought) (Iraq: Ministry of Culture and Information, Dar el-Rashid, Art Series, 1979); Azzawi, Dia' al-, The Art of Posters in Iraq, a study of its beginning and development 1938-1973 (Iraq: Ministry of Culture and Information, Dar el-Rashid, Art Series, 1974); Bahnisi, Afif, Al-Fan wal-Qawmiya (Art and Nationalism) (Damascus: Ministry of Culture and National Guidance, 1965).

[6] Al-Fan al-Iraqi al-Mu'asser (Contemporary Iraqi Art), volume 1 - visual arts (Lausanne: Sartek, 1977).

[7] Ali, Wijdan, 'Modern Arab art: an overview', in Salwa Mikdadi Nashashibi (ed.), Forces of Change: Artists of the Arab World (Lafayette, CA: International Council for Women in the Arts, 1994), pp. 73-4.

[8] Kameel Hawa established al-Mohtaraf, an acclaimed graphic design firm, based in Saudi Arabia and Lebanon.

[9] For more information on OSPAAAL and other protest posters see Cushing, Lincoln, ¡Revolución! Cuban Poster Art (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2003); Frick, Richard (ed.), The Tricontinental Solidarity Poster (Bern: Comedia-Verlag, 2003); and Martin, Susan (ed.), Decade of Protest: Political Posters from the United States, Vietnam, Cuba 1965-1975 (California: Smart Art Press, 1996).

[10] Frick (ed.): The Tricontinental Solidarity Poster, p. 92.

[11] In an interview with the author, July 2006.

[12] In an interview with the author, January 2006.

[13] In an interview with the author, February 2007.

[14] Moussalli remained active until very recently, when his old age and eye problems did not permit him to pursue his painting with the same ardency and as new means of design and digital printing took over the market of leaders' portraits.

[15]Muhammad Ismail established after 1994 his own independent graphic design studio and continued to provide his services to Hizbullah's media office on a consultancy basis.

[16]See Chelkowski, Peter and Hamid Dabashi, Staging a Revolution: The Art of Persuasion in the Islamic Republic of Iran (London: Booth-Clibborn Editions, 1999).

[17] For further study on Hizbullah's allegiance to Wilayat al-Faqih, see Saad-Ghorayeb, Amal, Hizbu'llah: Politics and Religion (London: Pluto Press, 2002), pp. 64-8.

[18] Chelkowski and Dabashi: Staging a Revolution, p. 115.

Foreword by Fawwaz Traboulsi

204 pages (including 64 colored)

ISBN: 978 1 84511 951 5

Zeina Maasri's book is a key intervention in studies of visual culture and mass media in the Middle East.