The World Goes Pop at the Tate Modern in London offers a new perspective on pop art beyond the tired British-American male heroes. It sheds light on artistic interpretations of pop in wider contexts ranging from South America to Eastern Europe, among other peripheral geographies. In particular, we encounter a politicized version of pop artworks from the late 1960s, denouncing global social injustice in the Third World and civil rights abuses in the West, as well as subverting US-led imperialism, particularly the war in Vietnam.

However, though attempting to re-write a globally inclusive and politically explicit artistic expression of pop art, the curators omit a crucial political geography from the exhibition's narrative. The Middle East, particularly the Arab-Israeli conflict and the Palestinian struggle for justice, was indelibly linked with the global political moment of the late '60s, as well as to the related pop aesthetics the exhibition features. In their expressions of transnational solidarity, artists (some featured in the exhibition) often linked Vietnam with Palestine in a unified struggle against imperialism and Zionism. Yet this important political geography and these artistic expressions of solidarity are entirely absent from the exhibition. Why?

Is it just accidental? Or are the curators simply not interested in the artistic practices of the Arab world and/or in the region's politics? Or is there another explanation? It may of course be just a coincidence that the exhibition takes place in the Eyal Ofer Galleries at the Tate, named after the Israeli billionaire; and that the man himself has made a £10m gift to the Tate. And perhaps the fact that Mr Ofer was himself politically active in the period covered is just another coincidence -- even though he served as an intelligence officer in the Israeli Air Force from 1967 to 1973.

Doubtless the fact that the Conflict Time Photography exhibition on show last year in the Eyal Ofer Galleries at the Tate addressed a global history of modern conflicts -- representing at least 20 -- contained not a single reference to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is yet another such coincidence.

The "global justice" take that the Tate seemingly offers is a sham. The structural inequalities decried by the artists in the World Goes Pop exhibition are once again structured according to the geography of power in today's art world. The Tate curators, for all their "commitment", are complicit in reproducing the politics of global injustice in its -- or should that be 'his'? -- galleries. Once again, military brutality on the ground goes with erasure from the global map of art and its histories.

Figures:

Marcello Nitsche

I Want You 1966

Museu de Arte Moderna, São Paulo, Brasil

© Marcello Nitsche

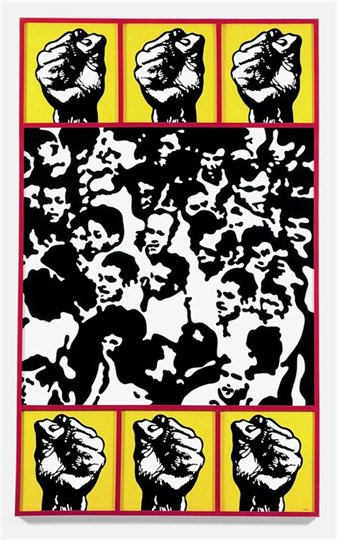

Claudio Tozzi, Multitude 1968

Museu de Arte Moderna, São Paulo, Brasil

© Claudio Tozzi