Last week Mikhail Kalashnikov died at the age of 94. Perhaps like many people who read the news, it was hard for me to associate a man, a person, with that name and undo the image of the ubiquitous weapon, otherwise known as the Ak-47. But then again, like many popular inventions the rifle carries the name of its designer.

In his post yesterday on Design Observer, Owen Edwards (co-author of the book Quintessence) comments on the ubiquity of the Kalashnikov design:

“Were it not such a killing machine, it might be called the Volkswagen Beetle of weaponry, though it has outlived the Beetle by quite a bit and is still going strong.”

In equating the Ak-47 rifle to the globally pervasive Beetle car, Edwards draws on the shared characteristics between the two designed objects: “simplicity, utility, and user-friendliness (and, in the case of the assault rifle, usee-unfriendliness)”. His comparison foregrounds modernist principles of functionality to validate the successful design yet ignores the symbolic and political factors that made the Kalashnikov rifle a ubiquitous icon of revolutionary struggle.

In the cold war, the Kalashnikov rivaled the M-16. It engaged the American model on battlefields across the (third) world and outbid it on the weapons market. More than surpassing the M-16 on grounds of functionality, the image of the Russian AK-47 conquered on the imaginary front of the ideological divide.

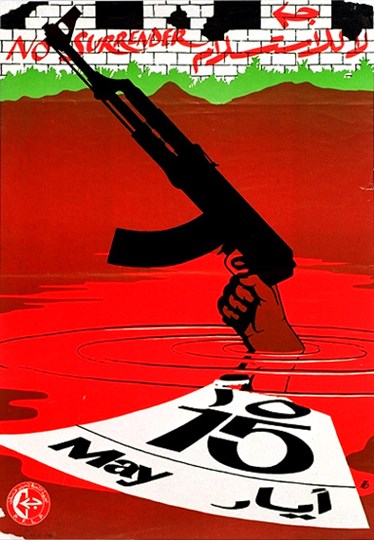

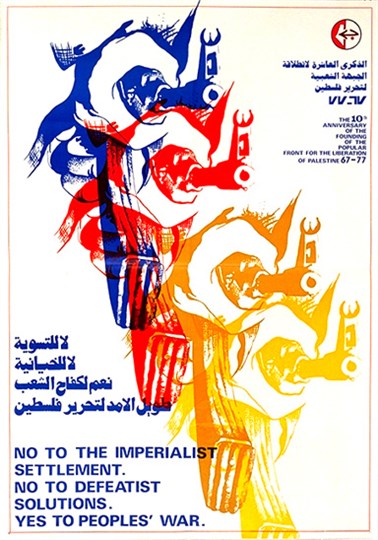

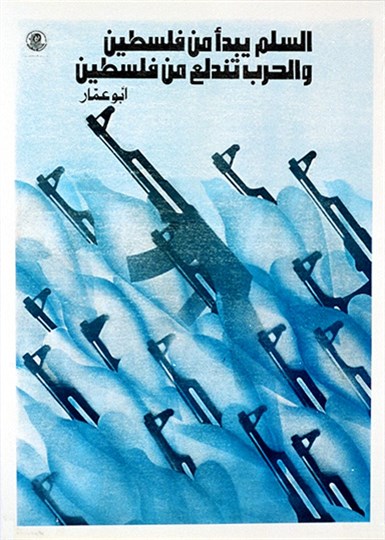

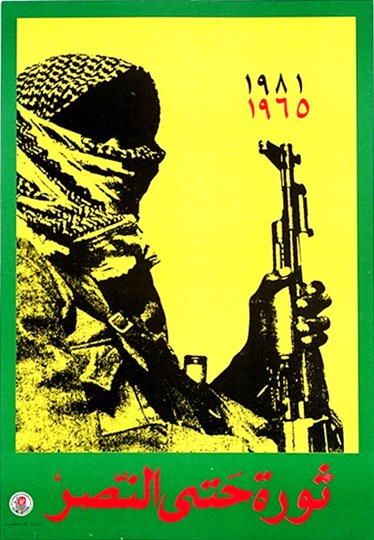

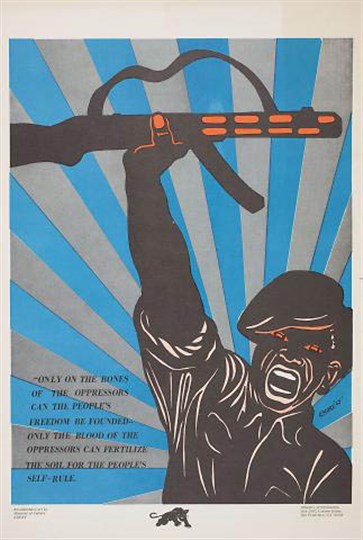

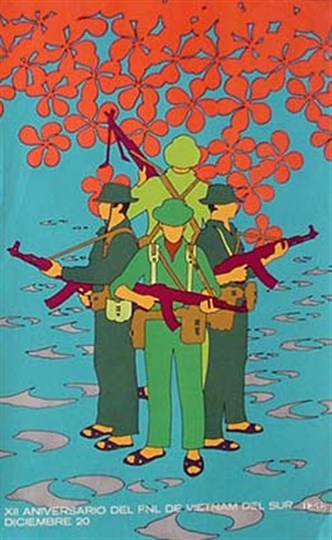

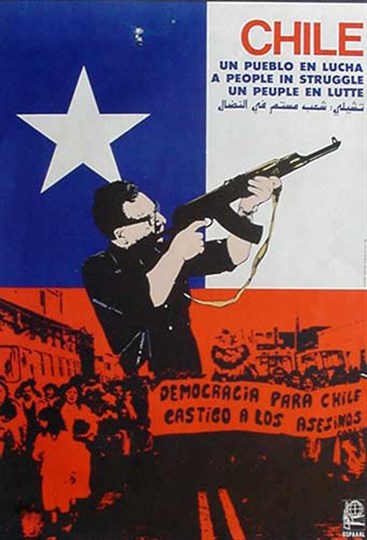

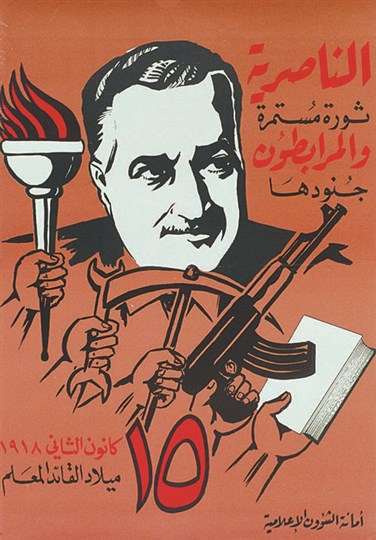

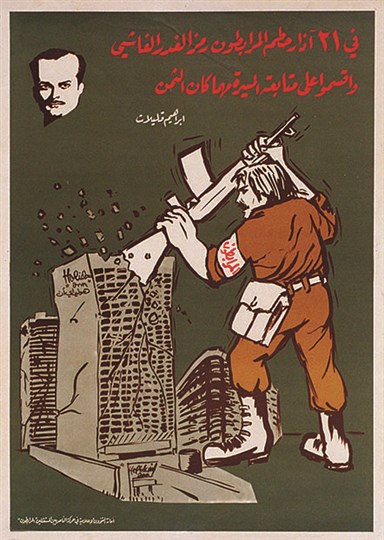

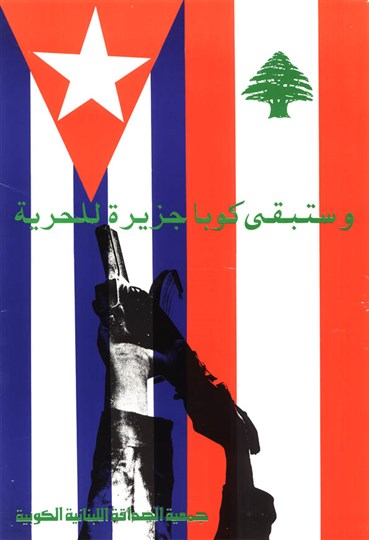

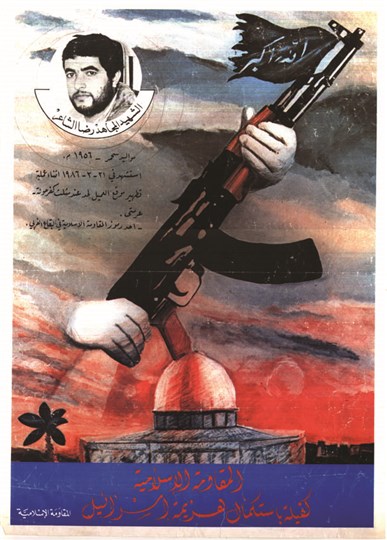

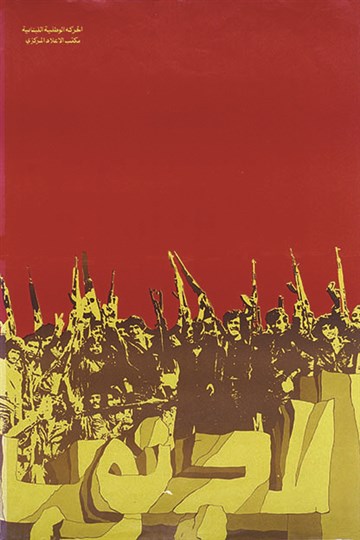

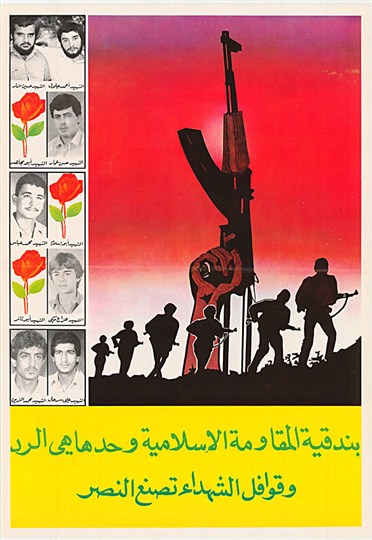

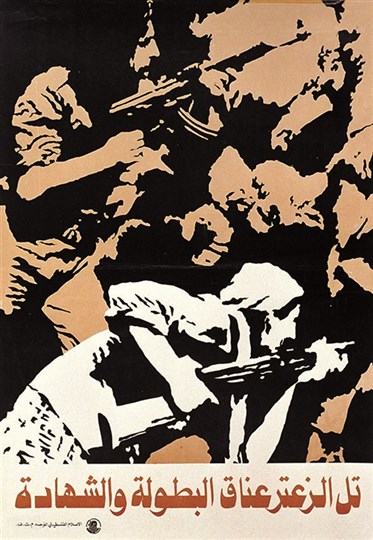

Held-up high by ‘freedom fighters’, to use the rhetoric of the day, the Kalashnikov, mediated as such, came to symbolize the armed struggle around which third-worldist and anti-imperialist liberation movements were mobilized. The image widely circulated in printed media––posters at the helm of these–– enabled by transnational solidarity networks that connected struggles in places like Guatemala, with people in Congo, Lebanon or Palestine and with geographies as far afield as Vietnam. The Ak-47 was a quintessential icon in the repertoire of signs, symbols and myths occupying the imaginaries of revolutionary fervor in and through which transnational political subjectivities of the cold war period were formed and actualized on the battlefront.

The story of the Kalashnikov makes an interesting case in the study of design history, it points to the complex relations between the object designed, its use value and the politics of its public appeal. To start with, it is outside the typical capitalist object-image relation drawn by advertising and branding that usually frames and often shortcuts such discussions. The Kalashnikov figured as a shared expression of a means of struggle in images advocating disparate political causes, it is not the intended object of promotion, yet gets promoted by mere contingency.

Moreover, despite the undisputed functionality of the rifle, the popularity of the Kalashnikov tells us more than a story of design ingenuity as Owen Edwards describes it. To a wider public than that of trained military, the Ak-47 invokes armed revolutionary struggle and not the durability of its barrel and parts on the battlefield. To a counter-public it conjures violence or the specter of terror drawn by the enemy’s weapon. In either case, the name is hardly linked to the creator but rather to the set of images and meanings associated to the rifle.

Finally, despite its violent intentions the Kalashnikov holds significance to the emerging conversations on design in its global dimension. Here again, the ubiquitous icon flows not according to the capitalist forces of a globalized economy, nor according to the modernist design claims of universal functionalism, it rather travels through political imaginaries formed in the visual trenches of the cold war.

The Kalashnikov story merits further study than allocated here but as it waits to be continued elsewhere, here are a few posters drawn from the Signs of Conflict archive and other collections on the world wide web.

---

Acknowledgement:

Posters used in this post taken from other collections than SoC can be found in the digital archives of the Palestine Poster Project Archives; OMCA collections and Ospaaal.