"All profound changes in consciousness, by their very nature, bring with them characteristic amnesias. Out of such oblivions, in specific historical circumstances, spring narratives . . . To serve the narrative purpose, these violent deaths [exemplary suicides, poignant martyrdoms, assassinations, executions, wars and holocausts] must be remembered/forgotten as ‘our own’."

Benedict Anderson. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism.

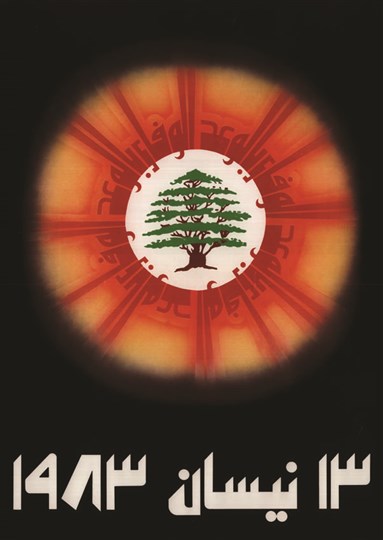

There is no official text that consensually explains how and why the civil war in Lebanon started, yet there is a consensus on an official date, 13 April 1975, that marks the beginning of the armed conflict. The date corresponds to a violent incident that arguably ignited the civil war, in which the Lebanese Kataeb party militiamen attacked a bus carrying Palestinian passengers, killing about 33 of them, presumably in retaliation for an attempt on the life of the party leader that same day. The bus was passing across Ain el-Rummaneh, an area in the eastern Christian sector of Beirut’s periphery, situated on the green line that ultimately divided the capital into two sectors.

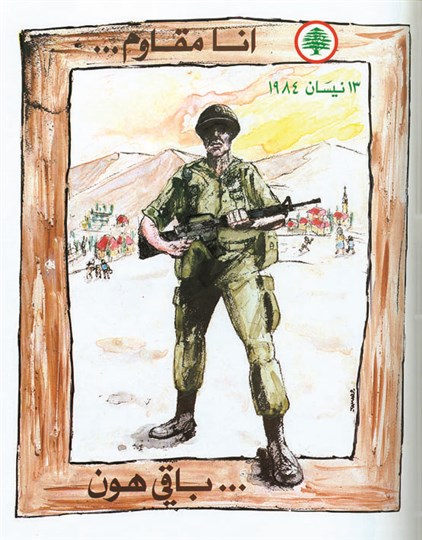

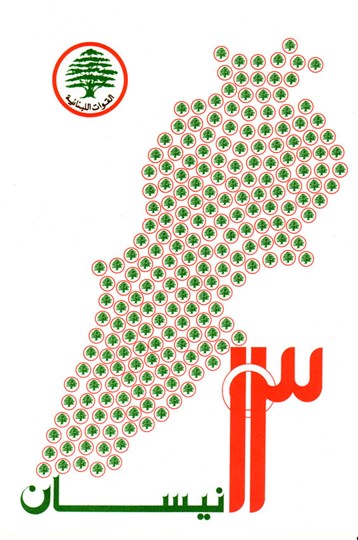

13 April 1975 has been the main subject of commemorative posters by the Lebanese Forces. The Lebanese Forces were formed in 1976 as a unified armed force of the Lebanese Front, which included the Lebanese Kataeb and other right-wing Lebanese nationalist parties. Seeing that the Lebanese Forces’ emergence is contingent to the outbreak of the war, it becomes evident why they gave importance to that date unlike other political factions. On 13 April, the Lebanese Forces commemorate their formation and recall their mission, similar to how other parties celebrate their founding date.

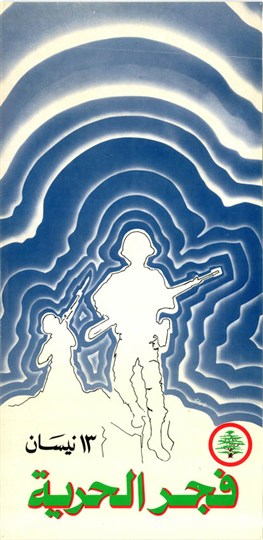

‘13 April, the dawn of freedom’ titles a poster issued by the Lebanese Forces circa 1983. The image, featuring two combatants in action, completes the poster message – ‘the dawn of freedom’ through military activity. A radiating energy emanates from the combatants, extending beyond the edges of the poster. They are metaphorically represented as a sun that has began its natural daily course – ‘the dawn’ – in 1975 to accomplish freedom. ‘Freedom’ can be understood within the front’s discourse of a sovereign Lebanon, free of ‘foreign’ armed forces, namely the Palestinian resistance and Syrian troops. The poster was issued in a period following the evacuation of the Palestinian Liberation Organization and the Syrian army from Beirut in September 1982. Yet just a few weeks later, Beirut was invaded by Israel. Lebanon endured in 1982 the invasion of its territories from its southern end up to its capital city. The accomplished ‘freedom’ that the poster suggests does not seem to be hindered by the Israeli occupation of Lebanese territories.

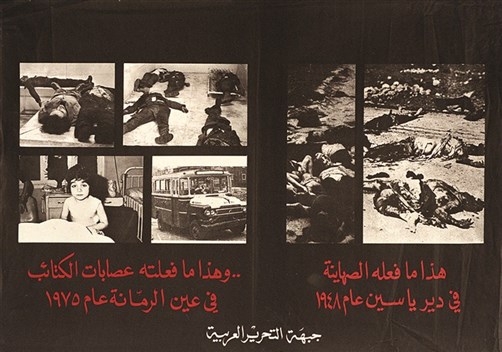

Aside from the many posters issued by the Lebanese Forces in commemoration of 13 April 1975, I have come across only two posters produced by other factions that address the same date and historical event. The first was issued by the Arab Liberation Front, a faction of the PLO, and links two violent events, disconnected in time and place, into one narrative. The apparent link is the civilian victims, as the photographs bluntly document. The text affirms: ‘This’ – the violent deaths in the photographs – ‘is what the Zionists have done in Deir Yassin in 1948’, and ‘This is what the Kataeb gangs have done in Ain el-Rummaneh in 1975’. The poster through a tight interplay of text and photography affirms that the victim is still the same: the Palestinian people. The authors of the poster claim this is how it was in 1948 and this is how it still is in 1975. The hostile image of ‘the Zionist enemy’ shared in the collective imaginary of the displaced Palestinian population is reinstated in this poster and transposed onto the Kataeb. Deir Yassin was the beginning of the Palestinian nakba (tragedy); by correlation, Ain el-Rummaneh, the poster implies, might be the beginning of yet another project of annihilation of the Palestinians. By collapsing two distinct events into one continuous narrative, the poster message ideologically connects the ‘aggressors’, Kataeb and Zionist, as equally threatening enemies of the Palestinian people. 13 April 1975 is condemned as a violent event in the Palestinian poster; it is inscribed within the community’s discourse of perpetual threats and suffering.

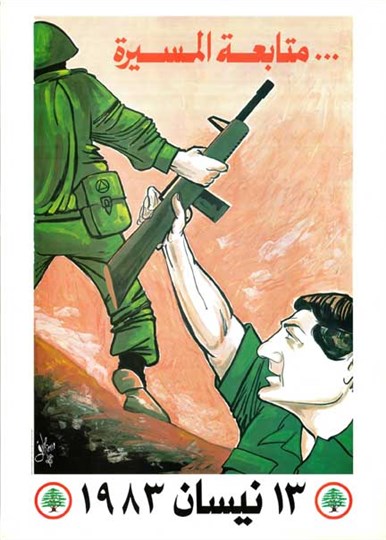

I return to another poster issued in 1983 by the Lebanese Forces. It builds on the 13 April date to evoke the memory of Bashir Gemayel, the founder and military leader of the Lebanese Forces. Gemayel was assassinated in September 1982, just after he was elected president of Lebanon. Around 1983, many posters were produced to mobilize the Lebanese Forces combatants, building on their memory and esteem for their lost idol. ‘Continuing the procession’ is the title of the poster: the journey to be continued is illustrated by the act of passing the rifle from one fighter to the other. The soldier in the foreground with a recognizable face is Bashir Gemayel in his LF military attire, his arm muscles flexed as he passes the rifle on to a generic figure of an LF fighter. The fighter has his back turned; he receives the rifle and heads upwards, outside the frame of the poster. We imagine him running and handing it to another similar soldier, and so on, ‘continuing the procession’ initiated by Bashir Gemayel, until the ultimate destination is reached. In other words, continuing the course of military combat to reach ‘freedom’ as expressed in the previous LF poster.

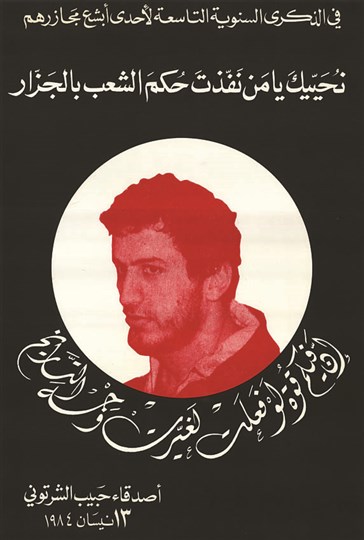

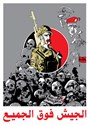

The myth of national hero constructed around Bashir Gemayel by his community was not uncontested. In fact, his many Lebanese adversaries regarded him as a traitor who allied with their national enemy, Israel. His coming to presidency, in conjunction with the Israeli invasion and occupation of Lebanon, was a distressing fact to many political communities, which publicly voiced their discontent to say the least and challenged the authority of the myth around his persona. This brings me to the second poster commemorating 13 April issued by the opposing camp. The poster was published in 1984 on the occasion of the ninth commemoration of 13 April; it is signed by ‘friends of Habib Shartuni’. Although it does not hold the signature of a specific party, the side that issued it is obvious. Habib Shartuni is a member of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party in Lebanon. He was behind the bomb blast that killed Bashir Gemayel in 1982 and was eventually arrested and put in prison. The poster does not deny his act, but rather honours it. Its title refers to a moral judgment laid by the people to name Bashir Gemayel as ‘butcher’ rather than victim. On 13 April, the poster recalls, nine years later, the Ain el-Rummaneh incident as ‘one of their most atrocious massacres’. The title incriminates Bashir Gemayel as the indirect perpetrator of these crimes, thereby deserving punishment, and salutes Shartuni for having executed the people’s judgment. The poster thus switches the roles between victim and criminal by subverting the legality of the official sentence on Shartuni to give instead moral legitimacy to his act.

13 April is celebrated by the Lebanese Forces as an awakening to national salvation, while the event is remembered and condemned as an act of violence by the opposing camp. The antagonism between the two sets of posters is clearly visible just by the contrast of colours – white and bright colours versus black. In each of the commemorative posters, the meanings of the historical event are linked and appropriated within the politics of a present moment to serve the issuing party’s narrative purpose.

This set of posters is one example among many commemorative posters with conflicting narratives over the same event/date produced during wartime Lebanon. The case of civil war reveals the impossibility of closure of an event into one single hegemonic narrative of commemoration. The meaning of an event while open to the field of discursivity is subject to political struggle and symbolic appropriation. Commemoration as such is an attempt by the parties in power to fix meaning and arrest the flow of signification around a certain event. Here, the politics of commemoration joins the politics of signification or the battle over truth.

*****

Text extracted from Z. Maasri (2009). Off the Wall. pp. 75–78.

Part of this text was originally published in German under the title "Gewalt Erinnert / Vergessen: Libano 13 April 1975" in the newsprint of the thematic symposium "Re-Education: You too can be like us" at the Hebel Am Ufer, Berlin, in 2008.